One of The Irish Heretic's goals is to focus on the cultural foundation of Notre Dame football—the Catholic faith. There’s a lot of commentary in the Catholic digital world about the University of Notre Dame losing its Catholic identity—and there can certainly be a discussion about academics under the Land O’ Lakes agreement. Nonetheless, I surmise that many who make such comments have likely never set foot on the Notre Dame campus.

I remember my first time on campus very vividly. I grew up a Notre Dame football fan. I aspired to play football for the Fighting Irish, being a cradle Catholic from the Midwest. I grew up watching Notre Dame football on NBC. I was 8 years old when the movie Rudy came out—Hey, that could be me! In high school, I was a poor student who never took my studies seriously and procrastinated too much.

Furthermore, I was an average, undersized football player who was merely shifty due to my smaller stature. By senior year, the University of Notre Dame wasn’t in the cards for me. Naturally, I still followed the Irish. Brady Quinn was the Quarterback of the Fighting Irish in my first year of community college. I can remember “The Bush Push” in 2005 and how USC cheated to beat Notre Dame.

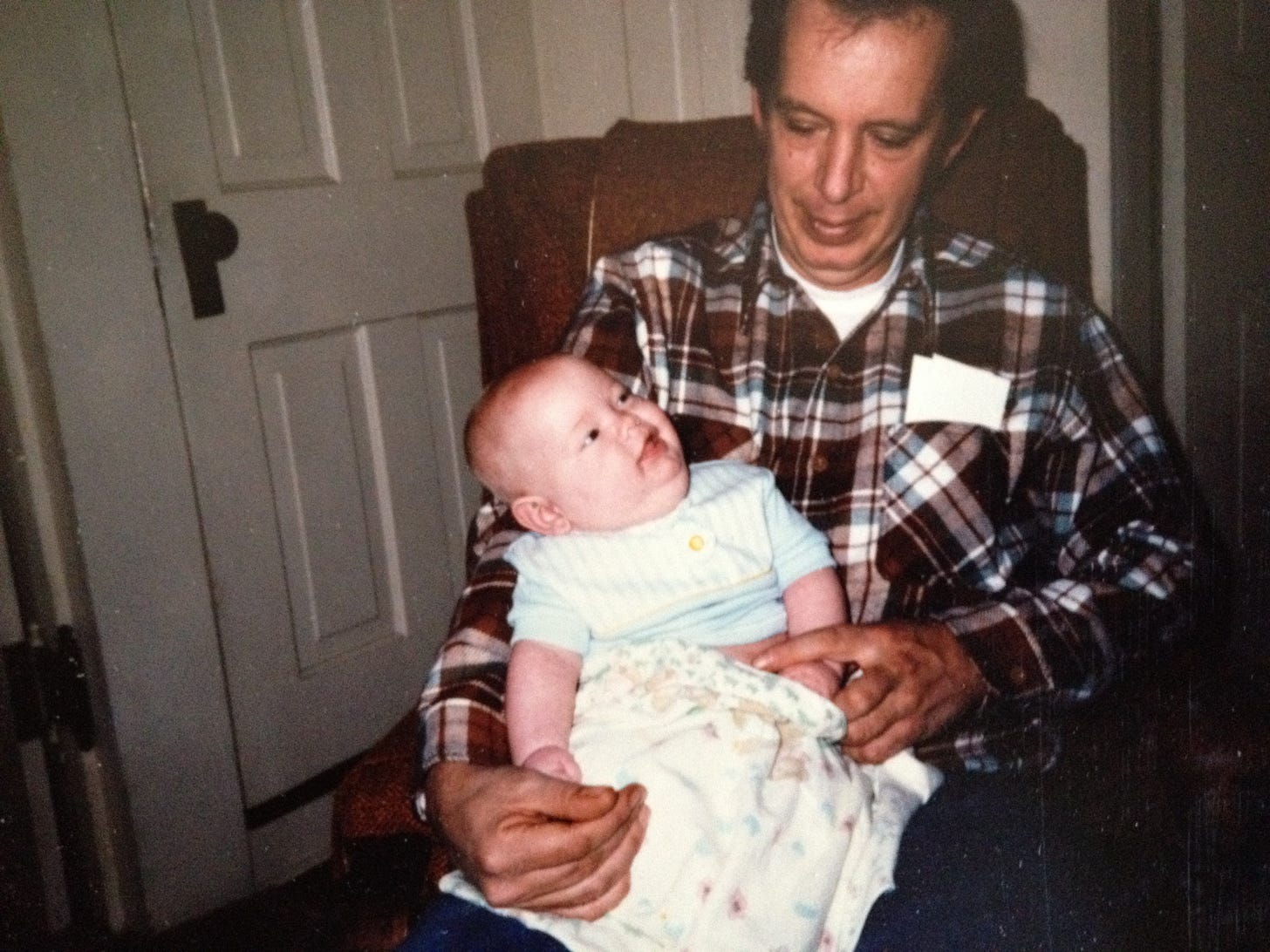

I eventually found myself at Southern Illinois University, where I was a Saluki. I was still a procrastinator; I wanted to live the good life. I wanted to be average. In September 2009, I was having some medical troubles that ended with me going into surgery to have my gallbladder removed. My Dad was waiting with me in the pre-OP room. I remember telling Dad, with a tremble in my voice, being scared, “This is the worst day of my life.”

“Son,” with a chuckle in his voice, “you’ll have worse days.”

The following week, I played campus intramural flag football.

In March 2010, during our Spring Break, I visited a friend near Seattle, Washington. I was tremendously excited, having never been to the Pacific Northwest and being a fan of grunge rock music. The plane landed; I settled in, and my friend took me to the college where they were working to show me around. My brother called me while I was on the campus tour. I was busy, so I ignored the call. My sister immediately called me: I thought, “That’s odd.” So, I picked up the phone call.

“Sit down. Dad is dead.”

I told this story once to a group of Scouts during a talk on resilience—I quoted Mike Tyson, who is attributed with the following: “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”

Life had punched me in the mouth. I became depressed and flunked out of college. (Remember, I only wanted to be an average student, so I didn’t have far to fall). I came home and got a job at the telephone company—AT&T, a year away from graduating with my Bachelor’s degree.

There is a life irony here that I have wrestled with for more than a decade: My Dad’s death changed who I was for the better. I love my Dad— I love him. I can’t explain it, but Dad's death sent me to the rock bottom of mediocre, so the only thing I could do was slowly climb out of it. I got a job. I paid bills. I met my future wife and got married. I remember announcing at my wedding reception, on November 3rd, 2012, after hearing there were some Notre Dame fans in attendance (one of them being Gabriel Rubio’s uncle): “Notre Dame has defeated Pitt in OT.”

I could no longer be a procrastinator; I could no longer be average. I was the husband—this was the beginning of my family.

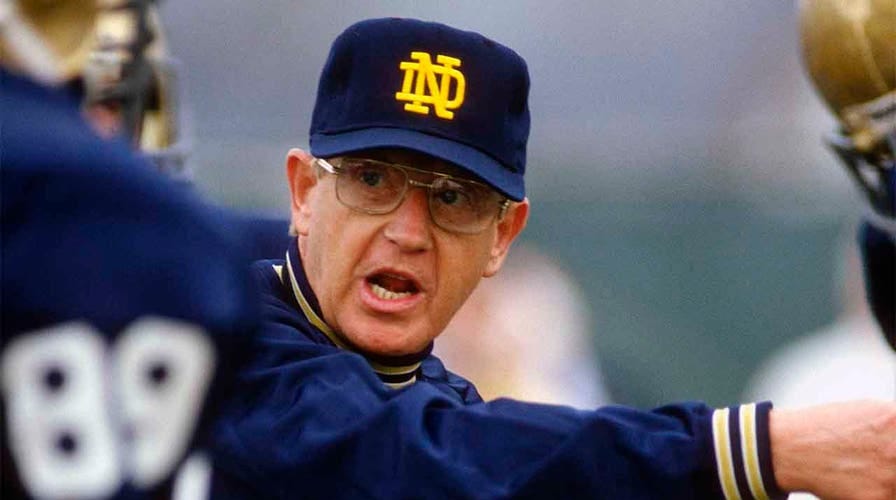

Lou Holtz writes in his autobiography, quoting 1 Peter 4:13:

Saint Peter commanded us to “rejoice” in our suffering, and not to “be surprised by the painful trial you are suffering, as though something strange were happening to you.” It is a natural part of life, a part that, as long as it doesn’t destroy you, builds character and helps you define your priorities.1

Dad’s death did not destroy me. In fact, it made an adult adolescent decide to reprioritize his life and become a man.

I returned to college. There was a difference when I walked into the room during this second stint. I wanted to be the best academically in the room. I realized how hard I worked was a reflection of myself and my family, a reality that, prior to my Dad’s death, would have never occurred to me. I graduated with Cum Laude honors, which is quite a feat after flunking out. I wanted to continue my studies, so I earned my master’s degree in Theology, earning Summa Cum Laude honors.

Now, I am a husband and a Dad, teaching my kids to give glory to God and to rejoice in our sufferings. There is a value in hard work—that can only be fully realized by the end of it. Iron sharpens Iron.2

It’s a paradox. I love my Dad, and I miss him. I wish he could meet my kids, but oddly, I wouldn’t be the man I am today if I didn’t lose him. It’s a mystery that I’ll never understand on this side of the eschaton.

There is no doubt that, as we close out 2025, many of you have suffered. Many of us will experience suffering in 2026: Hold Fast the Faith, Hope in God, and remember, Love Never Fails

The Irish Heretic is stacked within Missio Dei. If you would like to continue to receive posts, podcasts, etc., go to manage your notifications & manually opt into The Irish Heretic: college football’s heresy—but authentically Catholic.

Lou Holtz, Wins, Losses, and Lessons: An Autobiography (Kindle Edition), 133.

Proverbs 27:17