ST. KATERI, MAVERICK PRIEST, & SIOUX SISTER – THEIR PASSIONS FOR VOCATIONS

Special to Missio Dei Catholic. The Article is written by Beth Lynch

The Article, republished with permission, was originally featured in the December 2021 edition of “The Pilgrim,” the official newsletter of Our Lady of the Martyrs Shrine. The Shrine is located in Auriesville, New York. For more information about the shrine, please visit: https://www.ourladyofmartyrsshrine.org/

Beth Lynch is the Pilgrimage Coordinator and Museum Manager at Our Lady of Martyrs Shrine.

This did not come easily to Tekakwitha – living her vocation as a consecrated virgin.

Before she was baptized “Catherine” or Kateri, she had never even heard the phrase. Yet she shunned marriage to any of the native men in the Mohawk Valley, literally running from them as from mortal danger. She was badgered by her tribe for this irrational obstinance. Without a husband, there was no one to hunt for her, to provide food and clothing, to protect her from invaders, and to father children.

She stood firm. She knew that her body as well as soul was saved for a higher union she had yet to discover. When she learned from Jesuit missionaries that Christian women were not required to marry, the path to her vocation began to clear. The Holy Spirit, who had inspired and formed her in early life, rushed into her at baptism; her desire was to live as a spouse of Jesus Christ alone. This seemingly absurd lifestyle elicited mockery, assault, and mortal threats. She relocated to Kahnawake in Canada where native converts and catechumens lived under Jesuit instruction.

But even there, insistence persisted from other native converts. Finally, Father Pierre Cholenec saw the working of the Holy Spirit in her. He walked her through a discernment process that was punctuated with Kateri’s declaration: “Ah, my Father! I will not marry. I do not like men and have the aversion to marriage. The thing is not possible. I can have no other spouse but Jesus Christ.”

When Father Cholenec pledged to defend her in her newly realized vocation, he wrote: “I had removed the soul of Kateri from a strange purgatory and placed her in a sort of Paradise.” Kateri went on to take a vow of perpetual virginity and was further validated in her vocation when she encountered the Religious Hospitalers of Saint Joseph in Montreal. She wished to form such a community with her native companions where they would live together, pray, do penance, and perform acts of charity.

A religious order of native women was an idea centuries ahead of its time. Undaunted, and perhaps prophetic in the laity’s role in the Church today, Kateri maintained a little group of women who lived and prayed as if they were a vowed religious community. Kateri Tekakwitha died a consecrated virgin in 1680. After her death, and because of Kateri’s influence, one of these women pronounced the vows of a Sister at the Congregation of Notre-Dame in Montreal.

Fast forward 200 years to the Sioux reservations of the Dakota Territory. There, a maverick priest was conceiving a radical idea: an order of Native American nuns, trained as nurses, who would care for the bodily and spiritual well-being of their own people.

He was Father Francis Craft - a member of the Sons of the American Revolution who had rudimentary training as a physician and was a veteran of three wars before he was out of his teens.

His call to the priesthood from the battlefield was not easily realized. He spent six years as a Jesuit novice, received some formation with the Benedictines, and was finally ordained in 1883 as a diocesan priest specifically to minister to the Indians in the Dakota Territory. There he enthroned the Sacred Heart of Jesus as its True Chief, signing it in his own blood. He quickly realized the corruption and competition among government agents, protestant missionaries, and Catholic hierarchy. He aggravated all of them by his outspokenness against their injustice to the Indians. He was intelligent, quick tempered and arrogant, notably paranoid, articulate in confrontations, sometimes assaultive.

And he was Mohawk by ancestry – his grandmother was a full blood. Thus, did Father Craft declare his mission: “I became an Indian to save the Indian.”

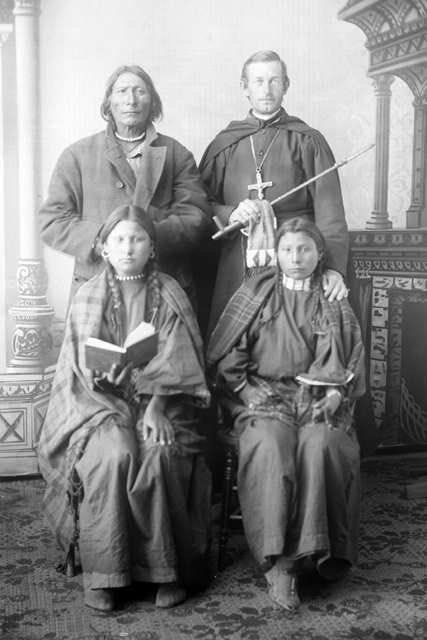

Faithful to his vision of training Native sisters to care for their own, he organized the Congregation of American Sisters, officially founded by his adopted Sioux sister, Josephine (Sacred White Buffalo) Crowfeather. Father Craft trained them as nurses, arranged for Benedictine formation, and was their spiritual advisor. His efforts were met with controversary, prejudice, and insufficient funding. Yet he marveled throughout: “Indian faith is pretty solid. I wish I had more of it.”

In March of 1890, sorely in need of funding, he traveled by train for a lecture tour on the east coast where he hoped to raise awareness and donations.

He made a stop, however, in Fultonville, NY. By horse and buggy, he arrived at the nascent Jesuit shrine called Our Lady of Martyrs founded just a few years before. As a former Jesuit, he continued to read the Messenger of the Sacred Heart (from which The Pilgrim originated) which carried updates about the Shrine.

On the holy ground where Kateri Tekakwitha was born, Father Craft prayed for the vocations of these Sioux novices. To each of them, he sent clippings of willows from the Shrine, encouraging them to pray to Kateri to strengthen their vocations.

He received a response from Josephine. She had taken her vows, and took the name Catherine, thus sharing with Tekakwitha the same patron saint, St. Catherine of Siena. She became the Prioress of the order.

Tensions on the reservation culminated with the Massacre of Wounded Knee later that year. True to his mission of “becoming an Indian to save the Indian,” he intervened and was lanced through both lungs. Accepting this as a fatal wound, he requested that he be buried in the trench with the Indians. But a priest refused to officiate. “He seemed quite put out,” Father Craft wrote, “that I preferred the Indians to the white dead.” Father Craft lived to officiate at the death of his beloved Mother Mary Catherine who died of tuberculosis in 1893.

Mining the archives of Our Lady of Martyrs Shrine revealed a letter from Father Craft published in The Pilgrim describing Mother’s death at the altar of convent chapel in the Dakota Territory: “She thanked God for giving success to the congregation through trials similar to those which Catherine Tekakwitha suffered. She had her sisters sang a hymn in honor of Catherine Tekakwitha, and Mother waited at the altar to join her Mohawk sister in triumph.”

Over the next several years, the warp and woof of the beleaguered “Indian problem” caused the order to dissolve. Father Craft lost his faculties as a Catholic priest. These were reinstated when he was assigned as pastor of a quiet parish in East Stroudsburg, PA. There he spent the last 18 years of his adventuresome life, much beloved by his parishioners.

A 2003 survey taken of Native American vocation by the United States Conference of Catholic Bishops listed 34 religious sisters, 27 priests, and 74 deacons. They can to some degree trace this success to Catherine Tekakwitha and Josephine Sacred White Buffalo who laid the foundations for Native American vocations.

Perhaps the most august is that of Archbishop Charles Chaput (Prairie Band Potawatomi), the first Native American serving in that role. Some have made pilgrimages to the Shrine: Retired Deacon William Gaul (Mohawk) served both the Albany Diocese and the Knights of Columbus of Saratoga Springs for many years and participated in annual pilgrimages. Father Michael Jacobs, S.J., the first Mohawk Jesuit, frequented the Shrine with Mohawk pilgrims. Father Maurice Henry Sands (Ojibway, Ottawa, Potawatomi), Executive Director of the Black and Indian Missions Office, attended a Mohawk Mass in the Coliseum. Bishop Donald Pelotte (Abenaki), the first Native American Bishop, blessed a statue of then Blessed Kateri when the Kateri Center, now the Saints of Auriesville Museum, was expanded in 1986. Sister Kateri Mitchell (Mohawk) of the Tekakwitha Conference knows the Shrine well.

Even as they walked this holy ground at the Shrine where St. Kateri was born, causes for other Native American saints were progressing. Among them are the Apalachees among the Martyrs of La Florida, and Nicholas Black Elk, the Lakota Sioux who, incidentally, spoke well of Father Craft. Father Craft died in 1920, nearly 100 years before the 2012 canonization of St. Kateri Tekakwitha. No doubt she met him at his passing.

The intercession of St. Kateri knows no ethnic or racial boundaries. The prayers of many different tribes and tongues have been answered through her. Her intercession can be assured for those discerning a vocation, and for those who are encountering obstacles along the way. Her aid can also be called upon for those who, like Father Francis Craft, champion the cause.

Quotes and biographical information of Father Craft taken from Father Francis M. Craft – Missionary to the Sioux by Thomas W. Foley. 2002: University of Nebraska Press.

Native American Catholics at the Millennium: https://www.usccb.org/issues-and-action/cultural-diversity/nativeamerican/resources/upload/NA-Catholics-Millennium.pdf

St Kateri Tekakwitha, pray for us.

Thx