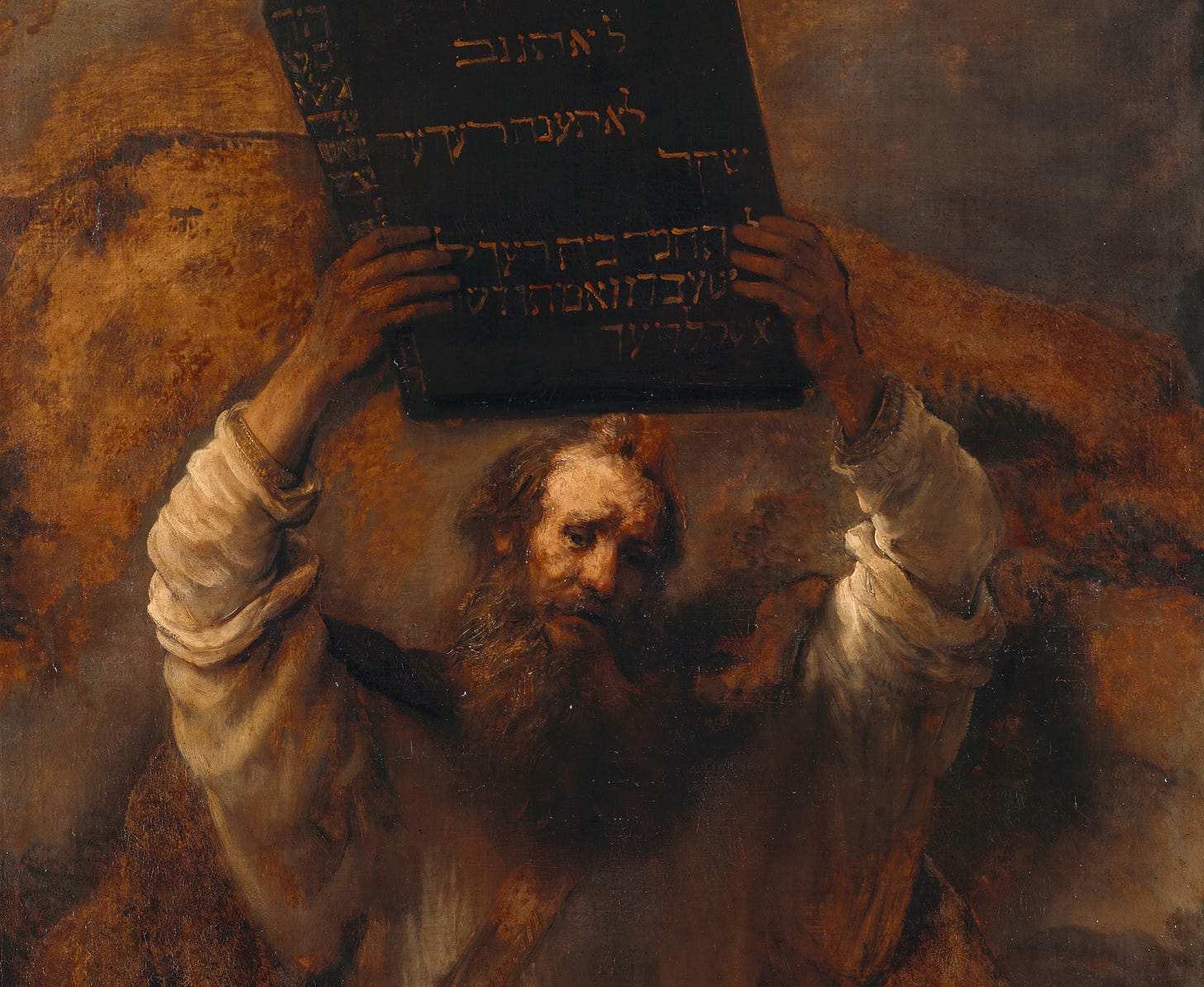

Sacred Scripture and Mosaic Authorship: Fact or Fiction?

Tradition has long taught that Moses wrote the Pentateuch—Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In relatively recent times, however, this belief has been questioned. Many modern scholars have scorned the idea of Mosaic authorship in favor of a more patchwork approach, claiming these books were written by a variety of authors, well after Moses’ death.

Is tradition right, or has modern biblical scholarship uncovered a new insight that our spiritual forefathers neglected to see?

For thousands of years there was very little doubt about the authenticity of Mosaic authorship. However, criticism of this tradition began to take firm room in the nineteenth century when liberal Protestant theologians began a quest to find the supposed “sources” of the Pentateuch. Their claim was that the Pentateuch didn’t date from the time of Moses (either 1400 or 1200 B.C.) but rather from the period after the Babylonian exile (sixth century B.C.).

The speculations and hypotheses of these scholars met their apex with the work of nineteenth century Protestant German biblical scholar, Julius Wellhausen. It was Wellhausen who solidified the so-called “Documentary Hypothesis,” which claimed that the Pentateuch and the sacred Jewish law were later, contrived additions to a previously primitive religion.

Although Wellhausen and those of his school could cite no factual basis for their theories, their persistence took root in scholarly circles to such an extent that they influence scholars even to this day, despite archeological and linguistic evidence that prove otherwise.

What Did the Church Fathers Believe?

Before discussing the Church Fathers, let’s consider what Jesus Himself said. He clearly believed in the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch, as attested in various verses in the Gospels including John 5:45-46: “Do not think that I shall accuse you to the Father; it is Moses who accuses you, on whom you set your hope. If you believed Moses, you would believe me, for he wrote of me.”

The Apostolic Fathers and subsequent Ante-Nicene Fathers seemed to have unanimously believed that Moses was the divinely inspired author of the Pentateuch. The only ancient records we have of criticism or doubt to Mosaic authorship comes from either heretical sects intent upon “curtail[ing] any Jewish claims to the divine authority of the Torah” or from pagans seeking to denounce the blossoming faith of Christianity.1

Origen of Alexandria, a second/third century A.D. theologian and one of the Church’s best-known early scholars, frequently wrote in affirmation of the Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch.2 Other early Church fathers of the second and third centuries who spoke firmly on Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch include Tertullian, Theophilus of Antioch, Clement of Alexandria, Melito of Sardis, Irenaeus, Justin Martyr, and many more.3

Mosaic Proof in Modern Archeology

In fairly recent times, archeological and linguistic discoveries have proven the Pentateuch to be authentic to the days of Moses. The literary style and structure of Genesis 1-11 clearly demonstrate a stylistic comparability to other literature of the early second millennium B.C., rather than a later dating of 900-400 B.C. as biblical minimalists have attempted to claim.4

Since the nineteenth century, archeological evidence has come to light which clearly displays a style of writing appropriate to the traditional dates for the composition of the Pentateuch. Comparable stories from Mesopotamian literature regarding creation (Enuma Elish), the flood (Epic of Gilgamesh), and the beginnings of the various human languages (Enmerkar Epic) have been shown to exist only in the early second millennium B.C.5 Furthermore, Genesis 12-50, which details the calling of Abram/Abraham and the further narratives of the Patriarchs, accurately demonstrate what scholars now know about the culture of the ancient Near East at the time in which Moses is said to have lived.

Eighteenth century French physician Jean Astruc was the first to develop the theory that the book of Genesis contained two source authors, based upon the two names for God used in the text, Elohim (“God”) and YHWH (“Lord”). Due to the existence of what he considered doublets (stories that were repeated, such as two creation accounts in Genesis 1 and 2) and seeming discrepancies in the text, Astruc maintained that although Moses did write the Pentateuch, editors after Moses’ time combined documents and thereby created the so-called inconsistencies.6

From there, the skeptical approach toward biblical criticism took root and began to flourish like weeds among the wheat (Matthew 13:24-30). The fad of hypothesizing that ancient texts could be separated into various sources became popular; for example the eighteenth/nineteenth century German scholar Friedrich August Wolf hypothesized the same multiple source structure for Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey.7 Building upon Astuc’s theory, other rationalist scholars began proposing more intricate ideas regarding the potential sources of the Pentateuch.

This speculation culminated in Julius Wellhausen, the scholar best known for developing what is now regarded as the Documentary Hypothesis. In 1878 he wrote his Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel with the goal of disproving the authenticity of the Law of the Jewish people. He claimed that the law of Moses was “a reflection of post-exilic Judaism and must therefore be considered a turning away from the prophetic religion which preceded.”8

It needs to be noted that the German liberal Protestant scholars of the eighteenth/nineteenth centuries openly displayed anti-Jewish sentiment, and Wellhausen was no exception. His entry in The Encyclopedia Britannica, simply entitled “Israel,” shows a clear example of his anti-Semitic attitude. He wrote:

Judaism is an irregular product of history … it is a mass of antinomies … As far as it can, [the Jewish law] takes the soul out of religion and spoils morality … self-chosen and unnatural, it does no one any good, and rejoices neither God nor man.9

The founder of American Conservative Judaism, Rabbi Solomon Schechter, has claimed the method of “Higher Criticism” begun by these nineteenth century German liberal scholars is more accurately described as “Higher Anti-Semitism” that seeks to denigrate Judaism by “denying all our claims for the past, and leaving us without hope for the future.”10 Theologian Joseph Blenkinsopp, in his work Prophecy and Canon, states:

Anti-Semitism pervaded and poisoned so much of German academic thought throughout the nineteenth century. Under the influence of radical ideology, public expression of anti-Jewish sentiment reached a new high at precisely the time when Wellhausen was publishing his reconstruction of Israel’s religious history.

Blenkinsopp then goes on to site many anti-Semitic examples pervasive during Wellhausen’s time, which later “made its modest contribution in due course to the ‘final solution’ of the Jewish problem under the Third Reich.”11

This was the virulent atmosphere in which the Documentary Hypothesis grew to maturity and took violent root in the university systems despite complete lack of external evidence.

The arguments of the Documentary Hypothesis are easy to refute.

Wellhausen expanded upon Astruc’s theory by claiming that because Genesis 1 speaks of Elohim, the transcendent name for God, whereas Genesis 2-3 speaks of YHWH, the more personal, immanent name of “Lord,” this indicates multiple authors. Yet it has now been proven through archeological discoveries that it was a common practice in the ancient world for a single author to attribute more than one name to the same god. In 1901 the Stele of Hammurabi, a series of legal codes written on a single stele dating to approximately 1754 B.C., was discovered in Persia. This single stele was clearly written by one author, yet as biblical scholar John Bergsma points out, there are multiple instances of gods and goddess referred to by different names in this one historical example. In the Egyptian Ikhernofret Stela, the god Osiris was also called Wennofer.12 Even the Koran uses multiple names for Allah, yet never has it been proposed that this document was written by anyone other than Muhammad.

Another argument of the Documentary Hypothesis, that of variations in literary style, is also easy to refute. Multiple literary styles between works of art may indicate literary mastery rather than multiple authorship. A modern example of how the same author can employ differing literary modes can be found in the works of celebrated nineteenth century author Mark Twain, particularly when comparing two of his famed “biographies.” The short story entitled “The Diary of Adam and Eve” tells the tale of the initial days of our first parents in a humorous, witty and fictitious way. This tale is a satire, not a work of history or true biography. In comparison, Twain’s last literary project was Personal Recollections of Joan of Arc, a seriously-toned, highly-researched novel which he considered his most important. The literary style of these two works are not similar, nor were they intended to be—yet they were indeed written by the same author.

Duplications and repetitions within the text have also been cited as indicating multiple authorship according to the view of the Documentary Hypothesis, despite the fact that these duplications were a popular literary style of the ancient world. In fact, “there is abundant evidence that ancient authors delighted in the kinds of repetitions, doublets, tensions, and wordplays that modern source critics deemed incontrovertible signs of multiple literary sources.”13

On June 27, 1906, the Pontifical Biblical Commission set forth a response to the Documentary Hypothesis.14 Detailed in scope, the Commission ultimately denied the theories set forth by Wellhausen and his followers, arguing that “the modern arguments used to support the Documentary Hypothesis were insufficiently strong to overturn the tradition of Mosaic authorship.”15 Instead, the Commission agreed with St. Jerome, who in the fourth century postulated that the verse in Deuteronomy where it states Moses died had been added by the scribe Ezra under divine inspiration.16 The Commission stated that, in the spirit of St. Jerome, it is unnecessary to believe that Moses physically wrote every verse of the Pentateuch with his own pen. Moses could have employed secretaries; he could have used oral traditions to supplement various biblical scenes, such as those occurring before his birth; and later scribes could have made inspired modifications “in an effort to modernize the Pentateuch for later generations of readers.”17

In the end, given that this debate will never be resolved fully unless we uncover tangible archeological evidence, the primary question remains: does it truly matter which human being wrote the Pentateuch? Scripture is composed by the hand of man, through the divine inspiration of the Holy Spirit. The Spirit can—and does—inspire prophets such as Moses, but He also inspires anonymous editors and redactors. Although God uses the talents, historical contexts, and circumstances of His authors to convey His truths, in the end it is His truths only that remain within the pages of Sacred Scripture. As for the name of a human author … well, in the words of William Shakespeare, “a rose by any other name would smell as sweet.”

Jeffrey L. Morrow, “The Modernist Crisis and the Shifting of Catholic Views on Biblical Inspiration,” in Letter & Spirit, Vol. 6: The Truth and Humility of God’s Word (Steubenville, OH: St. Paul Center for Biblical Theology, 2010), 267. See also Edward Young, An Introduction to the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 1949 reprint 1989), 113 and 114; see also Newell Woolsey Wells, “The Ante-Nicene Fathers and the Mosaic Origin of the Pentateuch,” The University of Chicago Press/JSTOR, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3156483 (accessed July 14, 2019).

Origen of Alexandria, “De Principiis, Book III, Ch. 5,” New Advent, http://newadvent.org/fathers/04123.htm (accessed July 15, 2019).

Robinson, Essential Torah, 102; Catholic Encyclopedia, “Pentateuch,” New Advent, http://www.newadvent.org/cathen/11646c.htm (accessed July 14, 2019); Newell Woolsey Wells, “The Ante-Nicene Fathers and the Mosaic Origin of the Pentateuch.”

Scott Hahn and Curtis Mitch, Ignatius Catholic Study Bible: Genesis (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 2010), 13; K.A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, 2003), 459.

Hahn and Mitch, Genesis, 13; K.A. Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, 423-426.

Bergsma and Pitre, A Catholic Introduction to the Bible, 42.

Gleason Archer Jr., A Survey of the Old Testament (Chicago, IL: Moody Bible Institute of Chicago, 1974), 84.

Weinfeld, “Getting at the Roots …”, 1.

Weinfeld, “Getting at the Roots …”, 4; see also Kitchen, On the Reliability of the Old Testament, 485.

Solomon Schechter, “Higher Criticism—Higher Anti-Semitism” in Seminary Address and Other Papers (Cincinnati: Ark Publishing, 1915), 37 as quoted in Bergsma and Pitre, A Catholic Introduction to the Bible, 77.

Weinfeld, “Getting at the Roots …”, 41-42.

Wolf, An Introduction to the Old Testament Pentateuch, 79; see also Harrison, Introduction to the Old Testament, 519. See also History.com editors, “Code of Hammurabi,” History Channel, https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-history/hammurabi#section_3 (accessed July 24, 2019); The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Code of Hammurabi: Babylonian Laws,” https://www.britannica.com/topic/Code-of-Hammurabi (accessed July 24, 2019).

Bergsma and Pitre, A Catholic Introduction to the Bible, 45. See also Harrison, Introduction to the Old Testament, 521-522; Cassuto, The Documentary Hypothesis, 80; Wolf, An Introduction to the Old Testament Pentateuch, 80-81; Pitre, Genesis and the Books of Moses.

Bergsma and Pitre, A Catholic Introduction to the Bible, 89; Catholic Encyclopedia,“Pentateuch.”

Hahn and Mitch, Genesis, 14.

Bergsma and Pitre, A Catholic Introduction to the Bible, 71.

In the end it comes down to the bias of believers vs. the bias of unbelievers. The unbeliever—as BXVI explains—argues existentially they cannot believe it to be true—it drives their works theses.

Personally, as a believer, whether Moses, committee, editor, St. Paul, not St. Paul, it doesn’t matter. So, whatever the conclusion—and I do have opinions, but when it comes canonical analysis—the Holy Spirit is the principal author of Sacred Scripture.

Well done Jenny!