Love and Imitatio Dei in the Classics

A Review of 'Dante's Footsteps'

Length is never an ultimate marker of fine literature. Certainly, some of Western civilization’s greatest works are beefy volumes: The Count of Monte Cristo, War and Peace, The Brothers Karamazov, and The Lord of the Rings, to name a few. But a well-written poem or short story can be just as powerful as any other art form.

With the short attention span gifted me by modernity and the limited time which everyone seems to scrape out of their daily lives for leisure, one is often forced to be selective of what one reads. And this effect of modernity, though the causes be problematic, is not entirely bad. It’s not bad to force yourself to develop a taste in literature, to censure your input of ideas and images so as to have more control over your output of thought.

St. Thomas More said that, since our minds are always occupied with something in our waking moments, it is important to occupy these minds with good, true, and beautiful thoughts. And as the priests at the Thomistic Institute remark, “It matters what you think.”

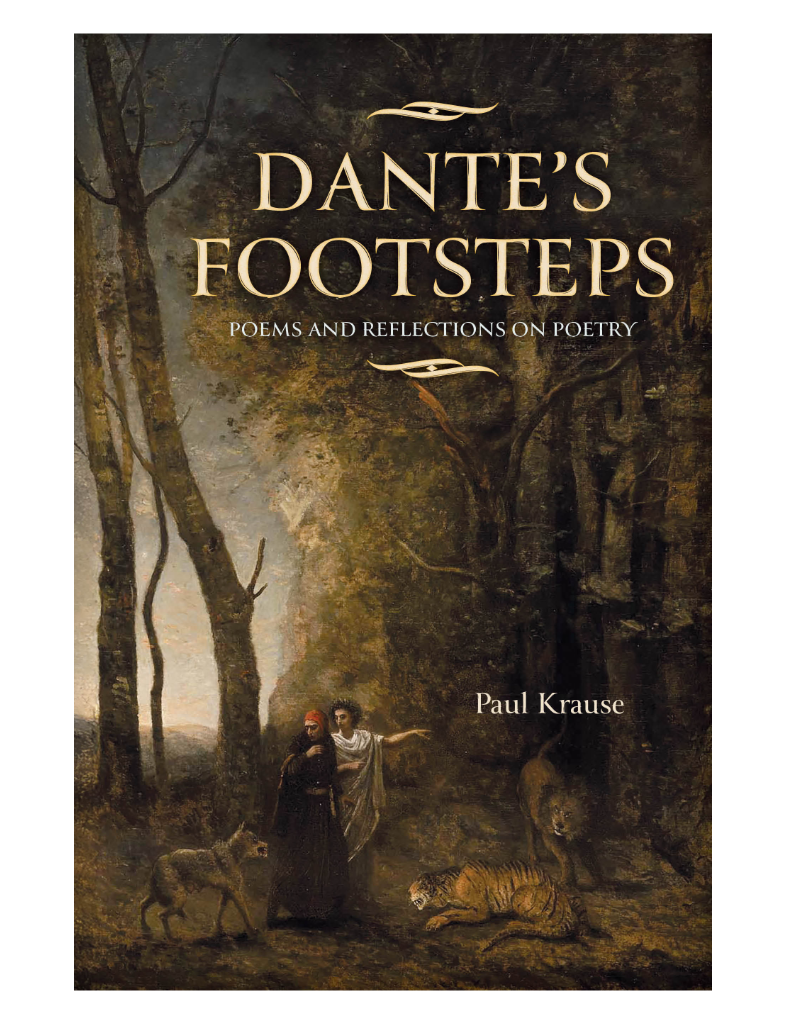

It’s wise to be discerning. Nevertheless, with the cultural dilemmas mentioned above, I find myself turning repeatedly to monographs, novellas, poems, and short stories to satisfy my literary cravings. One of the small books that I made time for this year was Paul Krause’s Dante’s Footsteps: Poems and Reflections on Poetry (Stone Tower Press, 2025). Krause’s collection of verse and essays is a concise yet broad-sweeping foray into the classics, whether it be recounting and analyzing their historical and social significance or weaving poetry that stands in dialogue with the wisdom of the ancients.

Krause’s nature poetry is his best, although there are some outliers that break that norm, including “Campaldino,” “Francesca’s Lament,” and the titular “Dante’s Footsteps.” Meanwhile, the essays are more engrossing than the poems. But any lover of lyricism will find a warmth in the rhyming and a crispness in the imagery these poems offer. The regular resurgence of motifs throughout Krause’s poetry is reminiscent of the recurring cycles expressed in nature itself.

In his essays, Krause covers myriad topics dealing with some of the finest poetry from the ancient, late medieval, and Romantic periods.

In his first few essays, Krause traces the linguistic and poetic development of love in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds. We hear how Homer, in the Iliad, offers the first documented use of the Greek word agape. In his body of work, agape refers to a love for the dead, a notion very Catholic in flavor. Later, when the Septuagint translators sought to render the Hebrew Scriptures into Greek, they selected agape as the term best fit to communicate God’s selfless, compassionate, all-consuming love. And it’s in that context that it is best known to this day. The reason the translators used agape, writes Krause, is that “Homer’s use of the term came closest to expressing a love rooted in compassion toward others.” If love is not geared toward the well-being of others, but is focused on the self, then we have vanity – not authentic love.

Virgil, revered both by Dante and by Krause, serves as a conduit to continue the conversation about love. In his essay “Virgil and the Christian Imagination,” the author cites St. Augustine of Hippo as having dubbed Virgil the “best and most renowned of all poets.” (In fact, Krause is widely influenced by Augustine, drawing from his Confessions, De Doctrina Christiana, and De Trinitate.) The author affirms that Virgil offers us something in accord with Christian theology, particularly Augustine’s. Namely, that “love is the most powerful force in the world.” For Augustine and the rest of the orthodox Christian thinkers (Krause cites Pope Benedict XVI’s Deus Caritas Est and the thought of Pope Saint John Paul II), the source and summit of love is Love Himself, the triune God, Who exists not in solitude but in a community of Divine Persons. And He is the most powerful force – in the entire cosmos! As Krause argues, we are not only made imago Dei, to be like God in our rationality, but we are further called to imitatio Dei, to be imitators of God and imitators of Christ.

In another essay, “Dante in the Digital Inferno,” Krause takes to task widely-held misconceptions regarding Dante’s contributions and significance to literature and creativity. It seems TikTok videos, among other venues, are to blame. (Truly shocking, I know.) In a sense, this essay serves as a sort of Snopes fact-check article that, instead of focusing on the current political echo chamber, comes to the aid of the besmirched reputation of a 13th-century Italian poet.

In the final essay of the book, Krause examines a common theme found among a few of the most renowned Romantic poets: the transience of worldly glory (often referencing Napoleon Bonaparte’s hamartia bent on dominating others) and their simultaneous lauding of Napoleon’s feats of power and military prowess. Keats, Byron, and Shelley prolonged the memory of a talented man who let vainglory tarnish his character. They did so in verse, both ridiculing and praising Napoleon. In so doing, perhaps they reveal their own struggles with ego and the thirst for recognition. Nevertheless, Krause notes the possible hypocrisy of both eulogizing the larger-than-life military leader and suggesting glory is fleeting all in one go. Echoing Scripture, he reminds us that, here below, all is vanity. And the darker implication of pursuing vainglory, which ultimately leads to cruelty and an attempt to demand control, is that it takes the path opposite to love.

In his essays as in his poetry, Krause’s overarching theme is that of love. The various forms of authentic human love, he writes, “allow us to practice imitatio Dei (imitation of God, who is Love).” This grandiose yet tangible theme steps beyond the confines of literature and into a broader social context, the web of relationships in which we all find ourselves.

Poetry is often, but not always, an inherent byproduct of love, and poetry can spur others on to love, whether that love be romantic or platonic, familial or social, political or patriotic. Krause correlates the rise of poetry with the rise of civilization. Social flourishing and philosophical rigor are preceded by a bloom in literary activity, and the author cites numerous cultures of the past in which this development can be clearly seen.

Literature, and especially poetry, Krause says, has the ability to ignite a “spiritual birth or resuscitation” within the individual and the nation. Poetry speaks of love, and people living in society are invited to love. The history of Christendom and all Western civilization is a tapestry of noble achievements as well as horrors. Yet, when people, and Christians in particular, actually live in union with the “Love which moves the sun and the other stars” as Dante once called God, when they live in imitatio Dei instead of living for selfish ambitions, then the dignity of the human person is acknowledged and each and every one is elevated in purpose.