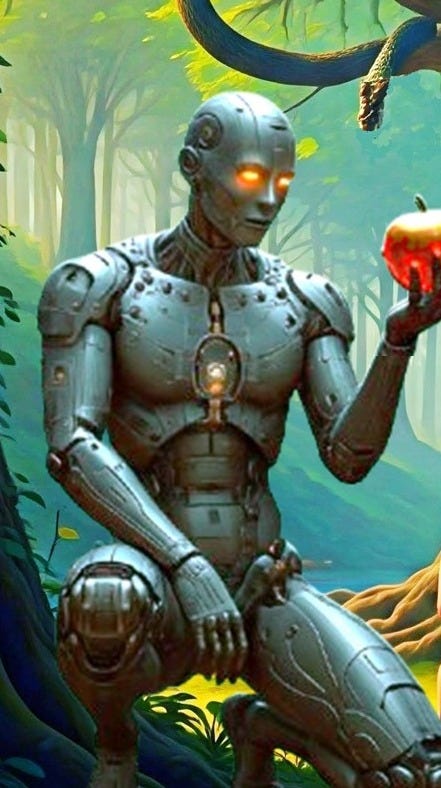

AI May Encourage Sin

By: Christopher M. Reilly

The following post includes edited portions of the copyrighted book AI and Sin: How Today’s Technology Motivates Evil.

It would take a great deal of mental effort to ignore the flood of news about artificial intelligence technology (AI) in recent years. Few technological developments in history have generated such a level of popular excitement, imagination, and also fear. Ray Kurzweil, computer scientist and author, has eagerly claimed that “we are going to expand intelligence a millionfold by 2045 and it is going to deepen our awareness and consciousness.” On the other hand, the sense of an impending, world-changing consequence is why sixteen leaders of world religions gathered in 2024 in Hiroshima, the site of a nuclear bomb explosion that ended World War II, to sign the Catholic Church’s document named The Rome Call for AI Ethics.

We can be open to new technologies while critically evaluating their impact on us. As Pope Francis said about the development of AI:

Human beings are, by definition, mortal; by proposing to overcome every limit through technology, in an obsessive desire to control everything, we risk losing control over ourselves; in the quest for an absolute freedom, we risk falling into the spiral of a “technological dictatorship.”Francis, Message of the Holy Father for the 57th World Day of Peace on January 1, 2024 (December 14, 2023), 4

One very significant moral aspect of AI is the way that it affects our understanding of ourselves, both as individual selves who communicate and live in a hyper-technological culture and as human beings. When we compare AI capabilities to our own intelligence and even our own agency as independent, responsible persons, we inevitably encounter existential questions. What does it mean to be a person? Or to be truly intelligent? Is intelligence the same as wisdom? Where does the truth that guides and orients us come from – the factual data and calculations that drive AI machines, the social relations and negotiated meanings of our communities, our intuition and imagination, the natural law, the transcendent reason of God, or some combination of all of these?

Guided by Church teaching, I don’t subscribe to either the breathless or the darker hyperbole about AI. Plus, moral responsibility can only be attributed to human beings who have the unique capacity for reason and free choice; this is a foundational principle of Christian moral teaching. What I am suggesting, however, is that the presence, development, and use of AI technology generally and significantly encourages a sinful disposition. The kind of sin I am referring to is acedia – at times a mortal sin according to St. Thomas Aquinas and one of the traditional “seven deadly sins.”

St. Thomas defines acedia as “sorrow about spiritual good in as much as it is a Divine good”(Summa Theologica, II-II, Q.35). Why sorrow? The intense desire for God’s love (whether fully conscious or psychologically sublimated) is coupled with a frustrated experience of that love due to a false sense that it is all too burdensome or distasteful. It is a refusal of “the yoke” of the Divine good – not of God in Himself, or of His love, but of enjoyment of God’s love, goodness, truth, and more. As a result, acedia leads at different times to apparently opposite behaviors: depressed idleness and an anxious inability to be at rest either physically or spiritually.

There are many ways that AI can and will encourage acedia, if not developed properly, as I describe in my book AI and Sin. Anthropomorphism – the tendency to experience non-human beings (e.g., AI chatbots and robots) as if they were persons – encourages a loss of appreciation for the uniquely spiritual nature of human intelligence. Computational and predictive intelligence will be inappropriately elevated in esteem, appearing to comprise the whole of intelligence. Such an illusion exacerbates emotional anxiety and anticipation, and it distorts evaluation of humanity’s intrinsic dignity and the sources of that dignity. With such a perspective, the inability of humans to compete in computations and prediction may discourage faith and hope in persons’ unique destiny and God-given place in the world (see the Church’s 2025 document Antiqua et Nova). Any confusion or degradation of human beings’ spiritual destiny is a threat to our understanding of our special relationship with God, appreciation of grace and its power in virtuous transformation, and focus on the divine good offered in the sacrifice and redemption of Christ.

In my next post, I’ll share more details about acedia. Later, we can examine in detail a few of the specific concerns regarding AI and how it may put us on a path toward acedia; these concerns include anthropomorphism, loss of privacy, involvement in personal relationships with AI applications, manipulation and deception by AI models, an increase in mediocrity and standardization, lost memories and meaning, bias in AI data and operations, and even a potential decline in trust in science and in the possibility of accessing truth.