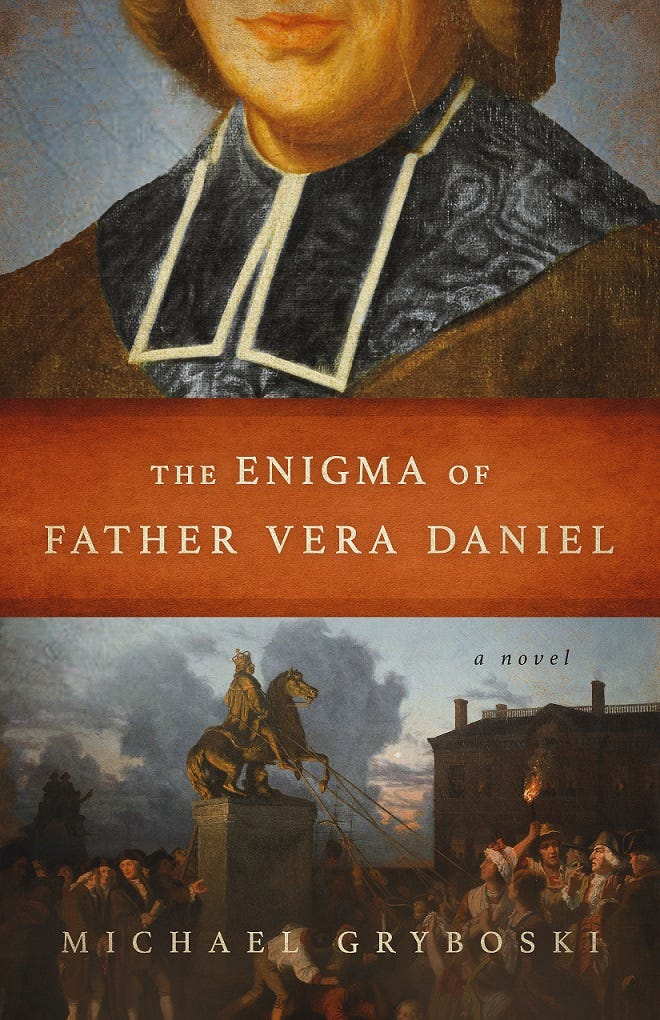

Our present day appears brimming with political polarization and violent confrontation. The contents of The Enigma of Father Vera Daniel address these issues so relevant to our day and age: issues of…

© 2025 Missio Dei

Substack is the home for great culture